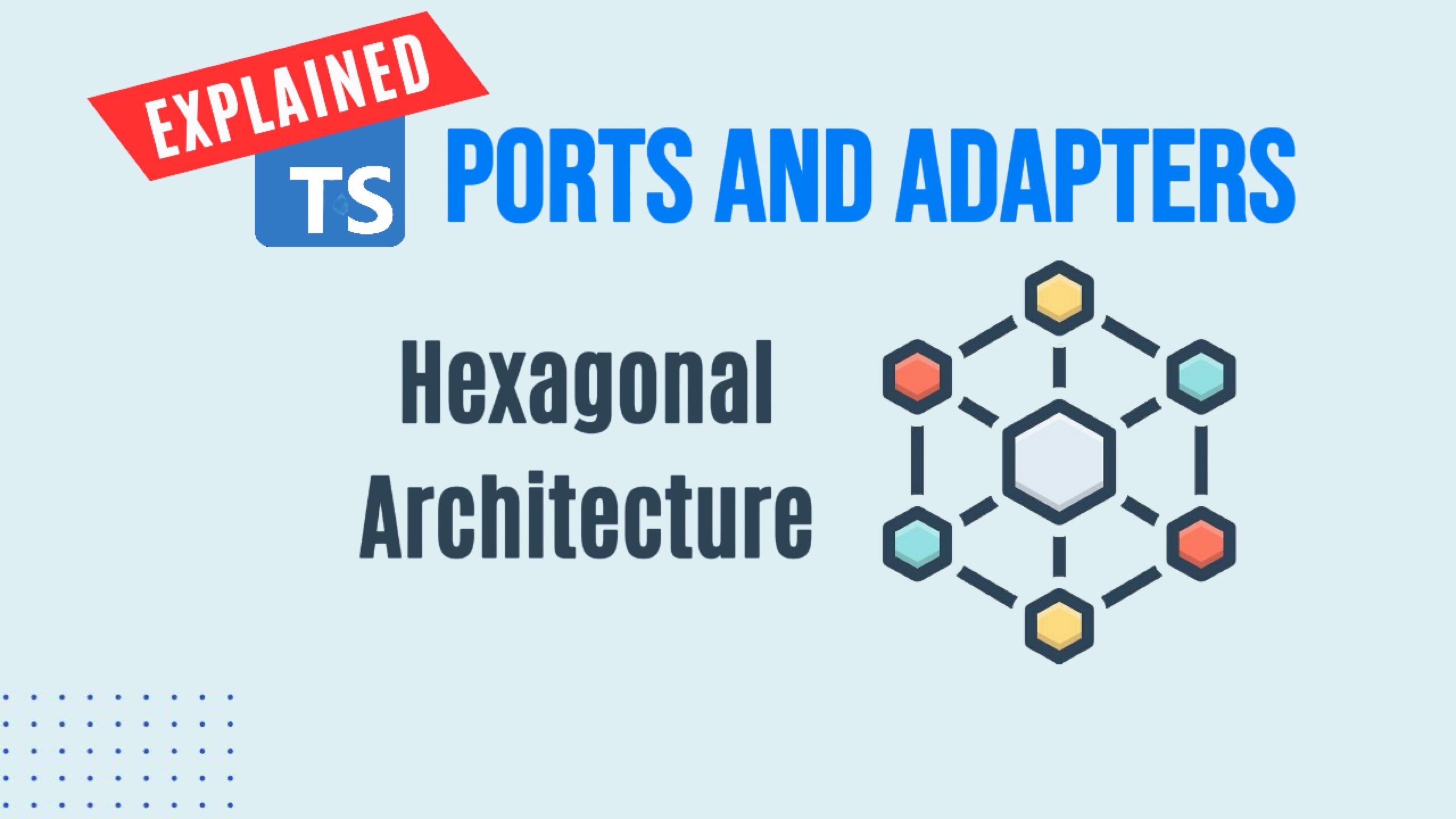

Future-Proof Your Code: A Guide to Ports & Adapters (Hexagonal) Architecture

Have you ever looked at your application and realized it’s become a tangled mess of tightly coupled code? You know the feeling—you need to change one small external service, but you’re terrified because that service’s SDK is hardcoded into dozens of controllers.

Imagine this scenario: Your application sends emails using SendGrid. It works great until management decides to cut costs and switch to Mailgun. Suddenly, you have to hunt down every single instance where SendGrid is used and refactor it to use Mailgun. It’s inefficient, stressful, and risky.

The problem isn’t the email service; the problem is tight coupling. Your business logic knows too much about how emails are sent.

To solve this, we turn to the Ports & Adapters pattern, also known as Hexagonal Architecture. This pattern helps decouple business logic from external dependencies, making your app flexible, testable, and future-proof.

What is Ports & Adapters?

Created by Dr. Alistair Cockburn, this architecture pattern visualizes your application as a central hexagon.

- The Hexagon (Application Core): This holds your pure business logic. It focuses on solving the domain problems, oblivious to the outside world.

- Ports: These serve as entry points for external interactions. They define what the application needs to do (e.g., “I need to send an email”), but not how to do it. In TypeScript, these are usually Interfaces.

- Adapters: These bridge the gap between the application’s ports and outside technologies (like databases, APIs, or mailers). They provide the concrete implementation of how something is done.

By using this pattern, your application focuses on the problem itself, ensuring the solution isn’t tied to a specific technology like SendGrid or Mailgun.

🚀 Complete JavaScript Guide (Beginner + Advanced)

🚀 NodeJS – The Complete Guide (MVC, REST APIs, GraphQL, Deno)

The SOLID Connection

This pattern is a practical application of the Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP), the “D” in SOLID. DIP states that high-level modules (your business logic/controllers) should not depend on low-level modules (specific mailer implementations). Instead, both should depend on abstractions (interfaces).

Let’s implement this in a Node.js/TypeScript Express API to see how it works in practice.

Tutorial: Decoupling an Email Service

We are working on a task manager app. The requirement is simple: notify an administrator via email whenever a user creates a new task.

Instead of hardcoding a mailer directly into our controller, we will use Ports and Adapters.

Step 1: Define the Port (The Interface)

When in doubt, use an interface. To decouple our controllers from specific mailer implementations, we first define what a mailer should look like.

We’ll create two interfaces: one for the notification structure and one for the mailer itself.

File: src/services/mailer/interface.ts

TypeScript

// Defines the structure of the email notification data

export interface IMailNotification {

to: string;

subject: string;

text: string;

html?: string; // Optional HTML content

}

// The Port: Defines the contract any mailer must adhere to

export interface IMailer {

send(mailNotification: IMailNotification): Promise<void>;

}

Now, our application core only knows about IMailer. It doesn’t know if the implementation is SendGrid, Mailtrap, or a carrier pigeon.

Step 2: Create an Adapter (The Implementation)

Next, we create a concrete implementation of that interface. For development, we’ll use Mailtrap (using the nodemailer library underneath). This is our Adapter.

File: src/services/mailers/mailtrap-mailer/MailtrapMailer.ts

TypeScript

import nodemailer, { Transporter } from 'nodemailer';

import { IMailer, IMailNotification } from '../../interface';

import config from '../../../../config'; // Assuming a config file holding env vars

export class MailtrapMailer implements IMailer {

private transporter: Transporter;

constructor() {

// Initialize nodemailer with Mailtrap credentials from config

this.transporter = nodemailer.createTransport({

host: config.mail.host,

port: config.mail.port,

auth: {

user: config.mail.user,

pass: config.mail.password,

},

});

}

// Implement the 'send' method required by the IMailer interface

async send(mailNotification: IMailNotification): Promise<void> {

await this.transporter.sendMail({

from: config.mail.from, // e.g., 'noreply@myapp.com'

to: mailNotification.to,

subject: mailNotification.subject,

text: mailNotification.text,

html: mailNotification.html,

});

console.log(`Email sent to ${mailNotification.to} via Mailtrap.`);

}

}

Step 3: The Business Logic (Use Case)

Now we need a place to handle the logic of creating a task and triggering the email. We use a “Use Case” pattern to keep our controllers clean.

This is where the magic happens: Dependency Injection.

Notice in the constructor below, we don’t ask for MailtrapMailer. We ask for the IMailer interface. This is Dependency Inversion in action.

File: src/use-cases/CreateTaskUseCase.ts

TypeScript

import { Request } from 'express';

import { IMailer } from '../services/mailer/interface';

// ... import your repository, config, logger etc.

export class CreateTaskUseCase {

private mailer: IMailer;

// private repository: TaskRepository;

// We inject the dependency here based on the abstract interface

constructor(mailer: IMailer /*, repository: TaskRepository */) {

this.mailer = mailer;

// this.repository = repository;

}

async execute(req: Request): Promise<void> {

const taskData = req.body;

// 1. Business Logic: Create the task in the DB

// const task = await this.repository.create(taskData);

console.log(`Task "${taskData.name}" created in DB.`);

// 2. Side Effect: Send notification using the injected mailer

// We don't await this because we don't want to block the response

this.mailer.send({

to: config.adminEmail, // Defined in your config

subject: 'New Task Created',

text: `A new task named "${taskData.name}" was created and is ready for review.`,

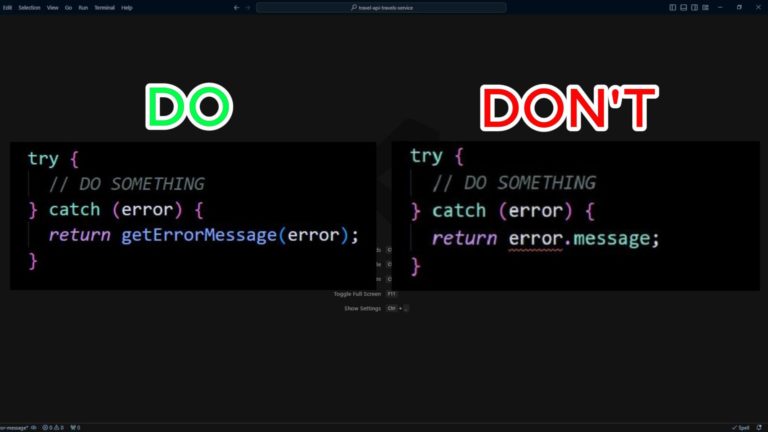

}).catch((error) => {

// Log error if email fails, but don't crash the request

console.error('Failed to send email notification:', error);

});

// Return result...

}

}

Step 4: Wiring It Up (The Controller)

Finally, in your controller or dependency injection container, you instantiate the specific adapter and inject it into the use case.

TypeScript

// In your controller file

import { Request, Response } from 'express';

import { MailtrapMailer } from '../services/mailers/mailtrap-mailer/MailtrapMailer';

import { CreateTaskUseCase } from '../use-cases/CreateTaskUseCase';

// 1. Instantiate the concrete implementation (Adapter)

const mailerImplementation = new MailtrapMailer();

// 2. Inject it into the Use Case

const createTaskUseCase = new CreateTaskUseCase(mailerImplementation);

export const createTaskController = async (req: Request, res: Response) => {

await createTaskUseCase.execute(req);

res.status(201).send({ message: 'Task created' });

};

Bonus: The Power of the Strategy Pattern

The beauty of this architecture is how easily you can swap implementations. This is often called the Strategy Pattern.

Let’s say during local development, you don’t want to actually hit Mailtrap’s API; you just want to see the email content in your terminal.

We can create a second adapter: ConsoleLogMailer.

File: src/services/mailer/console-log-mailer/ConsoleLogMailer.ts

TypeScript

import { IMailer, IMailNotification } from '../../interface';

export class ConsoleLogMailer implements IMailer {

async send(mailNotification: IMailNotification): Promise<void> {

console.log('--- [DEV MODE] Email Notification ---');

console.log(`To: ${mailNotification.to}`);

console.log(`Subject: ${mailNotification.subject}`);

console.log(`Body: ${mailNotification.text}`);

console.log('-------------------------------------');

// We return a resolved promise to satisfy the interface

return Promise.resolve();

}

}

Now, in your wiring logic, you can choose which adapter to use based on an environment variable:

TypeScript

import config from './config';

import { IMailer } from './services/mailer/interface';

import { MailtrapMailer } from './services/mailers/mailtrap-mailer/MailtrapMailer';

import { ConsoleLogMailer } from './services/mailers/console-log-mailer/ConsoleLogMailer';

let mailer: IMailer;

// Decide which strategy to use based on config

if (config.useConsoleMailer) {

mailer = new ConsoleLogMailer();

} else {

mailer = new MailtrapMailer();

}

// Inject the chosen 'mailer' into your Use Cases...

We just swapped out our entire email infrastructure without touching a single line of business logic in our Use Cases or Controllers.

Conclusion

By adopting the Ports & Adapters pattern, you move away from brittle, hard-to-test applications. You gain the flexibility to swap out third-party services, databases, or external APIs with minimal friction. Your business logic remains clean, focused, and unaware of the chaotic outside world.